In context of digital learning repositories we often times offer users a few ways to search learning resources without thinking much of why and for what purpose they would be using the repository.

Too many times repositories are developed with a glorious idea "if we build it, they will come". But to start with, do we really ask teachers whether they need a repository for digital learning resources?

Building a repository or a federation of them without asking this "raison d'être" is like creating a product to sell without a need or demand for it. That happens often, without doubt, but with the difference that there is a big marketing budget to create the need. Thus, teachers are stuck with bad looking search interfaces that hide potentially interesting technology without any needs and desires to use it.

To backtrack a bit, one should look at what teachers are doing in their work and how they are doing it. Ok, they teach, right. They have a goal, usually laid out in a curriculum, that they are set out to fulfill. They might have different requirements for the material to use; in some countries teachers have more freedom on choosing educational material than in others. To facilitate their job, teachers like to use the material that they are comfortable with and know well. They might use ready-made lesson plans by school book publishers or prefer to create their own material from bits and pieces.

Moreover, there are the routines to save time and efforts - information seeking, like learning, is a fundamental and high level cognitive process (Marchionini, 1995). People like to resort to something that they know does the job. Teachers are social animals, too, maybe a few hints from a colleague will settle a teacher for the day's task. Thus, the needs are rather contextualised (the given age, curriculum) and socially supported (accepted and negotiated educational practices, hints from colleague teachers,.. ).

Where does the digital learning material stand in this picture and how do teachers see the need for using a repository to better do their teaching? On the long term we are interested in looking at teachers' tasks in their teaching and see how digital learning resources repositories could better support teachers in their daily quest to make the learners better learners. Two main areas are concerned, namely information seeking and social information retrieval. We will argue that digital repositories should do more to offer social and contextual support for teachers and learners to discover relevant resources from a repository. But this blab is about looking into information seeking and the review on existing literature.

Information seeking, teachers and what a digital repository could offer?

When we think of a teacher preparing for a new lesson, we can think that it is part of larger information seeking behaviour, which is contextually driven, i.e. there is the national or regional curriculum, its topics, goals and learning activities to fulfill. The current information seeking research defines information seeking as a conscious effort to acquire information in response to a need or gap in your knowledge (Case, 2002).

For a teacher there is a diversity of support material available to fulfill the task, some of it being paper-based teaching material, some digital and others might relay on human resources. A teacher might also address a digital learning repository for the purpose of finding suitable digital learning resources. This teacher might already know exactly what he is looking for, a piece of material that he has seen before, or he might look for some motivational piece of information or some assessment material, for example.

However, often times digital repositories are not well prepared to serve different individual tasks that teachers might have at hand when they come to a repository. For that reason, more job-level analyses would be needed to look into individual tasks that teachers are to perform when they are using a learning resources repository. In general, the repositories have very little observation on patterns across tasks and contexts. So we ask, what are those general patterns that we can find across tasks that teachers are set out to perform at a digital repository?

Moreover, information seeking, in some cases, can be a social activity. Wilson (2005), for example claims that more information is communicated by word of mouth than is ever retrieved from databases. Many other researchers in the field of information seeking talk about its social layer. Hargittai & Hinnant (2006), who lay out a social framework for information seeking, argue that an “important factor influencing users’ information-seeking behavior concerns the availability of social support networks to help address users’ needs and interests. People’s information behavior does not happen in isolation of others.“

Thus, when we are looking into teachers information seeking tasks at the learning repository, it becomes important to think of the support for such social networks to tap onto. We can think of these networks in two different ways, as human resources themselves (such as getting in touch with an expert in a given field, etc) or as secondary support to help the teacher to find the suitable resource for the lesson. Or, like Peter Morville (2004) says; We use people to find content. We use content to find people. Information seeking behavior and social network analysis go hand in hand.

Information seeking ranges from forming question to gathering, synthesising and using information. It is usually cyclic and iterative process from seeking to gathering, refining questions, to evaluating and synthesising information to using it. A holistic view of information seeking process comes near to ideas of inquiry learning, both emphasising an iterative question-driven process of finding, managing and evaluating information. (Lallimo, et al. 2004).

Moreover, Kuhlthau (Wilson, 2004) also talks about search process in similar terms as educationalists, introducing the notion of the 'Zone of Intervention', similar to Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978), where the learner, when engaging in collaborative problem-solving with a guidance of an adult or more experienced student, can reach better level than without. Kuhlthau talks about five intervention zones, in some of which the advancement is dependent of collaborating with others, such as the librarian providing the quick reference or someone helping discovering potentially useful information resources.

We should further investigate how these zones of interventions could be supported in a digital learning repository when a teacher is looking for learning resources, or when a learner is there with his own information seeking intention to attain a task. We are interested in looking into supporting users in different ways, by designing better tools and interfaces, but also to build in support from fellow users.

This support could appear in different ways, such as "leaving traces" of information seeking patterns by other users or by creating social connections between users where they did not previously exist. The following can be envisaged: leveraging the previous search histories of other users; tapping into similarities in interest displayed by bookmarking action; looking into subjective relevance judgements such as annotations, tagging and end-user evaluations and ratings. Moverover, the use of existing social networks (such as expressed by using FOAF or FXML) should be supported, but more importantly, also the emerging ones, that could be detected by using social network analysis should be investigated.

---------

Case, D.O. (2002). Looking for informaiton: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs and Behavior, San Diego: Academic Press.

Hargittai, E. and Hinnant, A. (2006). Toward a Social Framework for Information Seeking. In New Directions in Human Information Behavior by Amanda Spink and Charles Cole.

Järvelin, K., Ingwersen, P. (2004). Information seeking research needs extension towards tasks and technology. Information Research, 10(1) paper 212 [Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/10- 1/paper212.html]

Lallimo, J., Lakkala, M. and Paavola, S. (2004) How to Promote Students' Information Seeking? ERNIST Answers archive, European Schoolnet.

Marchionini, G. (1995). Information Seeking in Electronic Environments, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Morville, P. (2004). Ambient Findability. http://www.digital-web.com/articles/ambient_findability/

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, T.D. (2004) Review of: Kuhlthau, C.C. Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. 2nd. ed. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2004. Information Research, 9(3), review no. R129 [Available at: http://informationr.net/ir/reviews/revs129.html]

Wilson, T.D. (2005). Review of: Ingwersen, P. and Järvelin, K. The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2005. Information Research, 11(1), review no. R189 [Available at: http://informationr.net/ir/reviews/revs189.html]

Links to other things I'm reading about the topic: http://www.furl.net/members/vuorikari/info_seeking

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

An interesting new acquaintance: the field of information seeking and retrieval

I read a review by T.D. Wilson of the book The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context, and decided to buy it for future reading.

This book introduces a new field called"information seeking and retrieval", which combines two existing ones, namely the research in information seeking and information retrieval. I have a feeling that this is something important for my studies, as I am not only interested in information retrieval in the context of a LOR, but I think the information seeking task at hand has important implications.

The reviewer explains information seeking being

Another important idea from the book, that the reviewer underlined, is that research should not be too narrowly system-oriented - otherwise it might run into the risk of being development of technology with no carefully analyzed use contexts. That is something that I have to also keep in mind, not to be too focused on one system that I study, but keep my mind and door open for further applicability. Looking forward reading the book!

Furthermore, I was reading about the book called Ambient Findability by Peter Morville, that my promoter wanted to bring into my attention. In an article dating in 2004 with the same name (what a stupid name, btw) he goes like this:

Very interestingly, when he says "Information seeking behavior and social network analysis go hand in hand." makes me nod my head. Yes, that is the way it goes and we need tools that help those two to better work together, and add information retrieval into it, maybe from the cognitive approach, as Ingwersen and Järvelin suggest. But for that, I have to read the book to know more.

Wilson, T.D. (2005). Review of: Ingwersen, P. and Järvelin, K. The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2005. Information Research, 11(1), review no. R189 [Available at: http://informationr.net/ir/reviews/revs189.html]

This book introduces a new field called"information seeking and retrieval", which combines two existing ones, namely the research in information seeking and information retrieval. I have a feeling that this is something important for my studies, as I am not only interested in information retrieval in the context of a LOR, but I think the information seeking task at hand has important implications.

The reviewer explains information seeking being

concerned with the discovery of the appropriate information for tasks, research, everyday life, etc., regardless of the way that information is packaged.

Another important idea from the book, that the reviewer underlined, is that research should not be too narrowly system-oriented - otherwise it might run into the risk of being development of technology with no carefully analyzed use contexts. That is something that I have to also keep in mind, not to be too focused on one system that I study, but keep my mind and door open for further applicability. Looking forward reading the book!

Furthermore, I was reading about the book called Ambient Findability by Peter Morville, that my promoter wanted to bring into my attention. In an article dating in 2004 with the same name (what a stupid name, btw) he goes like this:

It is this subtle power of context that intrigues me in the realm of networked information environments. We use people to find content. We use content to find people. Information seeking behavior and social network analysis go hand in hand. In today’s knowledge economy, learning and finding are powered by all sorts of invisible links between and among people and documents.

Very interestingly, when he says "Information seeking behavior and social network analysis go hand in hand." makes me nod my head. Yes, that is the way it goes and we need tools that help those two to better work together, and add information retrieval into it, maybe from the cognitive approach, as Ingwersen and Järvelin suggest. But for that, I have to read the book to know more.

Wilson, T.D. (2005). Review of: Ingwersen, P. and Järvelin, K. The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2005. Information Research, 11(1), review no. R189 [Available at: http://informationr.net/ir/reviews/revs189.html]

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Virtual co-learners may provide keys to faster, deeper learning

“The findings were that people learned much more with a supportive agent,” observes Nass. ”Some of our other findings indicate that a smarter co-learner (or agent), the one who gets the answer right, helps people learn more than dumber agents. It is clear that in any teaching or learning situation it is worthwhile to have a co-learner – someone else who appears interested.”

http://scil.stanford.edu/news/virtual10.htm

Yes, I want an agent based co-learner who would learn everything that I learn and never forget! Isn't it annoying when reading a text, half way through you say: well, I think I've read this text! That would never happen with the agent.

I already see myself having conversations with my agent: "Really, I know this already? So you mean I don't need to learn this anymore?".

In the future I might just kick back and let my virtual agent do all the communication and tackle the situations where I'm supposed to do something that I have already learnt.

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

school innovation

Learning styles are like a quick fix to understand something as complex as learning, and teaching, for that matter too. They are darlings of corporate training and something that managers look into when they are calculating ROI for professional learning and continuous training.

E-learning area seem to be the other domain where learning styles pop up often. Many times it is claimed that e-learning allows personalised learning, e.g. learner is presented with material that marches his/her learning styles. Commonly we see references to VAKT (Visual, auditory, kinaesthetic and tactile) or some dimensions like holistic vs. analytic or linear, etc.

I took a quick (fix) review on learning styles after a short discussion that I had with a colleague of mine. I, totally mistakenly (of course, not) mentioned something along the lines of learning styles, where my colleague mentioned "aren't they already so passe". Uuhmm, yeah, sure...

So I duck up some literature on the Web and realised: which learning style? There sure are many of them, Goffield et al. (2004), for example, identified 71 in the literature, out of which his team chose 13 most influential and potentially influential models of learning styles for a systematic and critical review.

After reading "Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning;

A systematic and critical review" one becomes humble about quick assumptions regarding learning styles. Table 44. presents these 13 Learning styles models matched against minimal criteria that was used in the review (p.139). Findings...

Oookey, seems like there is really something in this area of learning styles that hints that one should be rather wary and critical about quick fixes. Moreover, the plethora of models in the area should probably ring a bell. Along Coffield et al.

Coffield et al. are truly critical about this field of research, however, they don't, all together, through it to the waste-basket. They actually endorse some of the models which, instead of simplifying learning styles as anything like "deep-sealed features of the cognitive structure" or "components of a relatively stable personality type", see them more related to "learning preferences" or "learning approaches, strategies, orientations and conceptions of learning". They embrace these tools to help learners to gain more self-awareness and become more familiar with their metacognition, e.g. how to enhance their learning.

also

All right, now we are getting somewhere. Seems like it would be acceptable to say that people have learning preferences or "individual dispositions which influence the reactions of learners to their learning opportunities, which include the teaching style of their teachers." According to Bloomer and Hodkinson (2000) dispositions are both psychological and social. It is notable, however, that these individual dispositions constitute only a minor part of what can effect on learning.

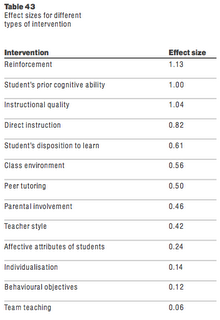

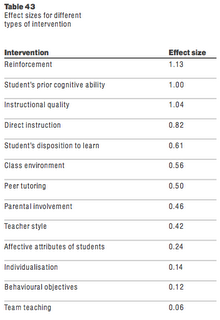

To enlighten other effects or intervention on learning, Hattie (1992, 1999) synthesised 630 studies. If individualised learning means offering learning according to students' learning styles, the average effect size is not significant for individualised teaching in schools (significant<0 .40=".40" br="br">

So, where does all this leave e-learning? Are we all just armchair psychologist looking for a quick fix to talk about how different ways of personalisation that ICT and multimedia offer can enhance learning? Maybe not, as the Coffield report leaves a back door open by saying that the potential of ICT to support individualised instruction "has not been fully evaluated".

Interestingly, this leads me where I want to go: look what ICTs can do. I will continue these notes with some reviews on papers on adaptive learning systems. For example, I'll look at this "Reappraising cognitive styles in adaptive web applications" that used Felder-Solomon Inventory of Learning Styles (ILS) instrument (which did not even make it to the 13 models studied by Coffield et al.) Oops, they say: "Contrary to previous findings by other researchers, we found no significant differences in performance between matched and mismatched students. Conclusions are drawn about the value and validity of using cognitive styles as a way of modelling user preferences in educational web applications." WoW!

It might be reasonable to note that in my research I'm not interested in adaptive learning or any of that, but I'm just doing this for the literature review to make my case of social information retrieval.

F Coffield, D Moseley, E Hall, K Ecclestone - Learning and Skills (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. Research Centre, Wiltshire, UK.

Bloomer M and Hodkinson P (2000). Learning careers: continuing and change

in young people’s dispositions to learning. British Educational Research Journal, 26, 583–597.

Hattie J. 1999 speach where the table is extracted by Coffield et al.

E-learning area seem to be the other domain where learning styles pop up often. Many times it is claimed that e-learning allows personalised learning, e.g. learner is presented with material that marches his/her learning styles. Commonly we see references to VAKT (Visual, auditory, kinaesthetic and tactile) or some dimensions like holistic vs. analytic or linear, etc.

I took a quick (fix) review on learning styles after a short discussion that I had with a colleague of mine. I, totally mistakenly (of course, not) mentioned something along the lines of learning styles, where my colleague mentioned "aren't they already so passe". Uuhmm, yeah, sure...

So I duck up some literature on the Web and realised: which learning style? There sure are many of them, Goffield et al. (2004), for example, identified 71 in the literature, out of which his team chose 13 most influential and potentially influential models of learning styles for a systematic and critical review.

After reading "Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning;

A systematic and critical review" one becomes humble about quick assumptions regarding learning styles. Table 44. presents these 13 Learning styles models matched against minimal criteria that was used in the review (p.139). Findings...

Only three of the 13 models – those of Allinson and Hayes, Apter and Vermunt – could be said to have come close to meetingthese criteria. A further three – those of Entwistle, Herrmann and Myers-Briggs met two of the four criteria. The Jackson model is in a different category, being so new that no independent evaluations have been carried out so far.

Oookey, seems like there is really something in this area of learning styles that hints that one should be rather wary and critical about quick fixes. Moreover, the plethora of models in the area should probably ring a bell. Along Coffield et al.

These central features of the research field – the isolated research groups, the lack of theoretical coherence and of a common conceptual framework, the proliferating models and dichotomies, the dangers of labelling, the influence of vested interests and the disproportionate claims of supporters – have created conflict, complexity and confusion. They have also produced wariness and a growing disquiet among those academics and researchers who are interested in learning, but who have no direct personal or institutional interest in learning styles. After more than 30 years of research, no consensus has been reached about the most effective instrument for measuring learning styles and no agreement about the most appropriate pedagogical interventions. p. 137

The main charge here is that the socio-economic and the cultural context of students’ lives and of the institutions where they seek to learn tend to be omitted from the learning styles literature. Learners are not all alike, nor are they all suspended in cyberspace via distance learning, nor do they live out their lives in psychological laboratories. Instead, they live in particular socio-economic settings where age, gender, race and class all interact to influence their attitudes to learning. Moreover, their social lives with their partners and friends, their family lives with their parents and siblings, and their economic lives with their employers and fellow workers influence their learning in significant ways. All these factors tend to be played down or simply ignored in most of the learning styles literature.

Coffield et al. are truly critical about this field of research, however, they don't, all together, through it to the waste-basket. They actually endorse some of the models which, instead of simplifying learning styles as anything like "deep-sealed features of the cognitive structure" or "components of a relatively stable personality type", see them more related to "learning preferences" or "learning approaches, strategies, orientations and conceptions of learning". They embrace these tools to help learners to gain more self-awareness and become more familiar with their metacognition, e.g. how to enhance their learning.

One of the main aims of encouraging a metacognitive approach is to enable learners to choose the most appropriate learning strategy from a wide range of options to fit the particular task in hand; but it remains an unanswered question as to how far learning styles need to be incorporated into metacognitive approaches. (p.132)

also

The positive recommendation we are making is that a discussion of learning styles may prove to be the catalyst for individual, organisational or even systemic change.

All right, now we are getting somewhere. Seems like it would be acceptable to say that people have learning preferences or "individual dispositions which influence the reactions of learners to their learning opportunities, which include the teaching style of their teachers." According to Bloomer and Hodkinson (2000) dispositions are both psychological and social. It is notable, however, that these individual dispositions constitute only a minor part of what can effect on learning.

To enlighten other effects or intervention on learning, Hattie (1992, 1999) synthesised 630 studies. If individualised learning means offering learning according to students' learning styles, the average effect size is not significant for individualised teaching in schools (significant<0 .40=".40" br="br">

So, where does all this leave e-learning? Are we all just armchair psychologist looking for a quick fix to talk about how different ways of personalisation that ICT and multimedia offer can enhance learning? Maybe not, as the Coffield report leaves a back door open by saying that the potential of ICT to support individualised instruction "has not been fully evaluated".

Interestingly, this leads me where I want to go: look what ICTs can do. I will continue these notes with some reviews on papers on adaptive learning systems. For example, I'll look at this "Reappraising cognitive styles in adaptive web applications" that used Felder-Solomon Inventory of Learning Styles (ILS) instrument (which did not even make it to the 13 models studied by Coffield et al.) Oops, they say: "Contrary to previous findings by other researchers, we found no significant differences in performance between matched and mismatched students. Conclusions are drawn about the value and validity of using cognitive styles as a way of modelling user preferences in educational web applications." WoW!

It might be reasonable to note that in my research I'm not interested in adaptive learning or any of that, but I'm just doing this for the literature review to make my case of social information retrieval.

F Coffield, D Moseley, E Hall, K Ecclestone - Learning and Skills (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. Research Centre, Wiltshire, UK.

Bloomer M and Hodkinson P (2000). Learning careers: continuing and change

in young people’s dispositions to learning. British Educational Research Journal, 26, 583–597.

Hattie J. 1999 speach where the table is extracted by Coffield et al.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)